The Horten Ho 229 is sometimes cited as one of the earliest examples of a “stealth aircraft” because its flying-wing design would have made it harder to detect by radar.

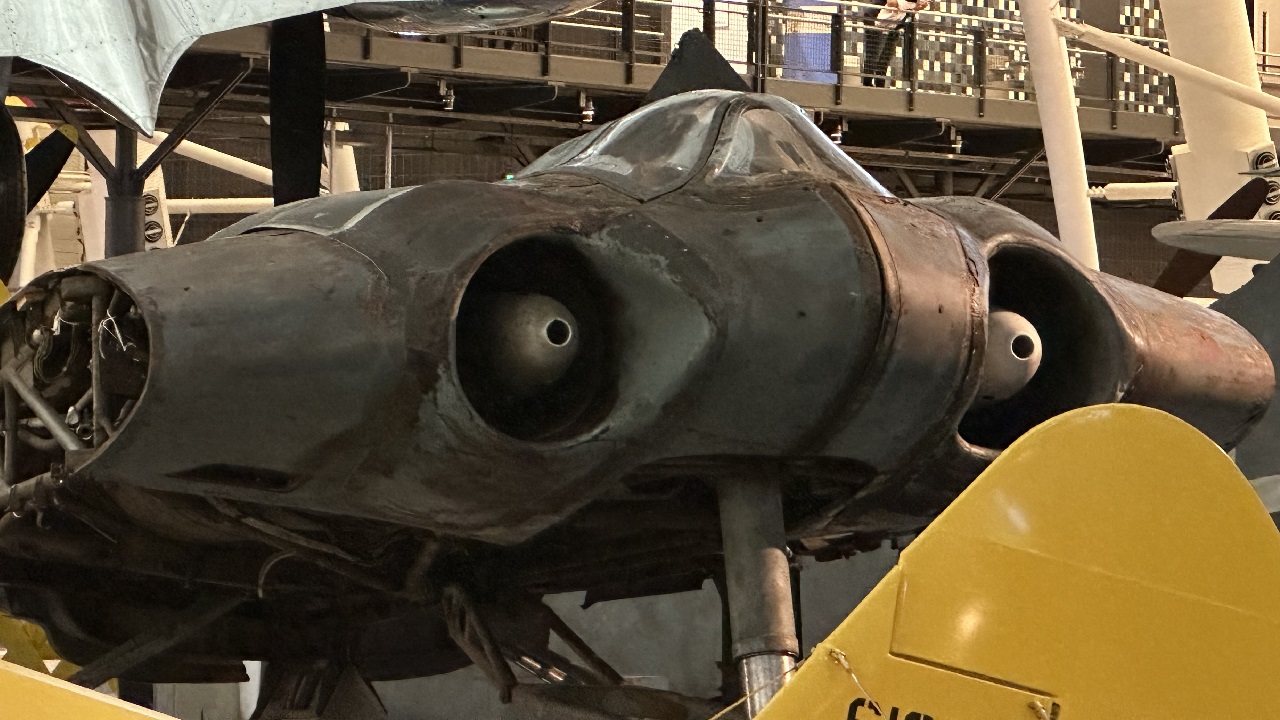

Look at the Ho 229: To gather details for this article, we made a special trip to the National Air and Space Museum just outside of Washington, DC, and did our best to get as near to the Horton Ho 229 on display as possible. The plane was so far away that recording a video was difficult. Nonetheless, the photographs below and above are authentic and were taken during our trip.

Check out the rest of our trip’s coverage for more intimate experiences with planes, including the SR-71, X-35, Bell X-1, and NASA’s Space Shuttle Discovery.

In the summer of 2020, the media criticized Trump because it seemed like he thought the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II was invisible to the human eye, which is untrue. Although “stealth” planes are visible, their radar signature has been drastically reduced thanks to new technologies.

Before the British discovered radar right before World War II, none of that mattered much. To give the Royal Air Force more time to respond to inbound German bombers, Winston Churchill had radar stations built around the English coast, which he dubbed “castles in the sky.”

With its initial success, German engineers began developing countermeasures for radar.

Walter and Reimar Horten, a brother-and-sister pair from Germany, were among those hired for this purpose. They directed a tiny team that created the revolutionary HoIX aircraft. While the prototype’s wings were constructed from solid plywood, the production model was to have been skinned with a sandwich material of thin plywood sheets and a core of sawdust, charcoal, and glue. Although it has a “high-tech” ring, the material was designed with radar absorption in mind.

It had dawned on the Hortens that the metal skins of contemporary aircraft at the time reflected the radar waves, so they set out to create materials that would cancel out the reflection. The plane had an interesting design, and its effectiveness in evading even the less advanced radars of the day is debatable, but it was still an impressive feat of engineering.

They had imagined a wing that could lift you into the air.

Too little, too late, ho 229

By the time they were done, the war was well underway, and the Nazis had already made more miracle weapons. Indeed, the Hortens weren’t given the same “red carpet” treatment as the German rocket experts. Hence, their efforts only amount to a little. The brothers didn’t start developing the Horten Ho 229 fighter plane until the war’s final months when Nazi Germany was already on the verge of collapse.

The Horten No. 9 (H. IX) was a Nazi “super weapon” that saw production beyond its initial prototype. The first completed prototype was a glider, then came single-seaters, and the final prototype would be a two-seater.

Most people now agree that the Horten Ho 229 was one of the first “stealth aircraft.” Its flying wing design would have made it harder for radar to find than other planes of the same size. While the aircraft had a greater wingspan than a fighter like the Messerschmitt Bf 109, its vision would have been similar to that of the Bf 109.

Despite ongoing construction, the Ho 228 V3 was never able to take to the air. Perfecting the plane would have made little difference anyway because Germany would have yet to be able to mass-produce it.

Following the war’s conclusion, the United Kingdom and the United States looked at several Horten plans.

As the war ended, the U.S. Air Force examined the airframe and three early Horten gliders, and in 1952, they gave them to the institution that would later become the National Air and Space Museum. The process of preservation did not start until 2011. After years of restoration, it is on exhibit, but it is difficult to view because it is not in a central location, and we could not capture footage that did the plane credit. You can see that we did our best with the photographs featured above and below.

The Horten brothers had offered their services to the British and American efforts to construct an airplane based on their design, but they had yet to be turned down. Due to restrictions on aircraft production in Germany, Reimar Horten relocated his expertise to Argentina. Yet, despite his persistence in developing his flying wing idea, something substantial came when he died in 1994.

When Northrop developed its N-9M one-third scale all-wing prototype, the U.S. Air Force looked into it and included it in the Northrop XB-35 and YB-35, experimental heavy bombers constructed for the United States Army Air Forces in the years following World War II. Northrop Grumman started working on the B-2 Spirit in the 1970s, long after they had abandoned the idea.