Biden Should Support European Strategic Autonomy

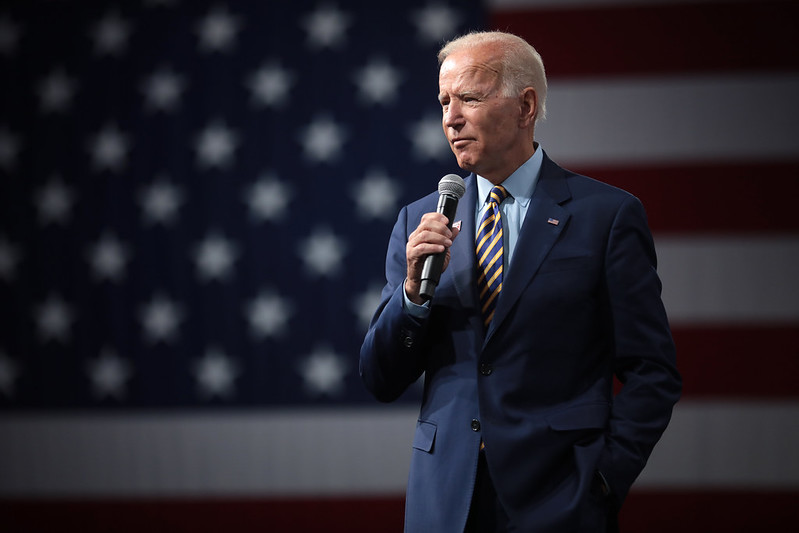

U.S. President Joe Biden traveled to Europe this month to start a series of meetings with European allies, his first international trip since entering office. Biden wrote his main agenda for the G-7 and NATO summits within the Washington Post, stating that both meetings are going to be squarely about “realizing America’s renewed commitment to our allies and partners” while working to endorse democracies around the world. As one might expect, summits of these types generally adapt flowery joint statements, group photos, and self-reassuring words of group solidarity. But, except for the U.S., trumpeting NATO’s longevity or going on great trans-Atlantic tasks is not sufficient. Instead of getting the Europeans on one page and making them follow the United States’ lead, the Biden Should Support European Strategic Autonomy.

This suggests getting rid of some bad habits and allowing Europe to require more responsibility for its affairs instead of inhibiting them. Military spending may be a prime example. Successive U.S. administrations have pressured European allies to extend their defense budgets to reduce the safety burden on Washington and extend NATO’s overall military capacity. While President Donald Trump will forever be referred to as the person who scolded Europe for pinching pennies on defense, U.S. presidents from as far back as Dwight D. Eisenhower are consistently frustrated with the continent’s unwillingness to satisfy U.S. demands. President Barack Obama once mentioned European powers as “free riders” who were reasonably good with outsourcing their defense needs. Obama and Trump, of course, have some extent.

When it comes to security expenditures, most European countries are not on par with the NATO standards. Excluding the U.S., only 10 out of 30 NATO members spend 2 percent or more of their gross domestic product on their defense. To take one among the foremost egregious examples: Germany, the most important economy in Europe, maintains a military that is still in a state of disrepair. As illustrated in Afghanistan, NATO as a corporation is very hooked into the U.S. for the major basic functions. The U.S., however, isn’t absolved of blame for this example. While European governments are predominantly liable for the state of their militaries, Washington has contributed to the matter by frowning upon — if not discouraging — Europe’s movement toward strategic autonomy.

The U.S. defense establishment, in effect, criticizes Europe for taking steps toward what Washington has long wanted it to do: boost the strength, lethality, and overall effectiveness of European militaries; therefore, the U.S. can spend longer on higher priorities within the Asia-Pacific region. President Biden has a chance to part ways with decades of ineffective U.S. policy in Europe, reinforcing the burden-sharing issues multiple administrations in Washington have purportedly sought to resolve. But to try to do so, the U.S. must do less for Europe, loosen the reins and stop taking issue with allies seeking to require the initiative — albeit NATO isn’t the only beneficiary. A unified European military budget for weapon development and inter-European training exercises should be praised, not condemned. Concerns about Europe coming out as a strategic rival of the U.S. are not very realistic.

But a feckless Europe dependent on the U.S. military, unable to try to do much of anything on its own, is extremely real. In the initiative to the U.S. election last November, the talk over European strategic autonomy flared up once more, as prominent European leaders voiced their views on what a change in power in Washington would mean for the ECU Union. In an article in Politico, German Defense Minister Annegret Kramp-Kannebauer trampled on Europeanist pretensions, saying that “illusions of European strategic autonomy must come to an end: Europeans won’t be ready to replace America’s major role as a security provider.” French President Emmanuel Macron was quick to retort that this wasn’t the position of German Chancellor Angela Merkel. It affirmed that “on the contrary, the changeover of Administration in America is an opportunity to still build our independence for ourselves because the U.S. does for itself.”

This is a reasonably facile debate, and both references to the U.S. were likely intended for domestic consumption more than as assertions of coherence in strategic thought. Moreover, notwithstanding some nuances, both Kramp-Karrenbauer and Macron were broadly asserting an equivalent policy within their statements: increasing Europe’s capacity in the realm of defense to require greater responsibility for security in its neighborhood. Most tiringly of all, the whole brouhaha could be avoided with a look at the history of European defense integration. Especially, the account of the abortive 1954 European Defense Community (EDC) illustrates that European defense integration is best viewed as a response to U.S. demands for a greater European contribution to international security than as a fracture within the transatlantic alliance. The purpose of the EDC was based on the U.S. demand for West Germany to collect itself and help in defense of Western Europe from the USSR.

Within the late 1940s, because the conflict intensified, the U.S. and USSR emerged as antagonistic superpowers with military forces spread across the world. In Washington, this new order gave rise to the strategy of containment, first laid at the Truman doctrine, which aimed to stop the spread of communism by confronting communist regimes across the world. Soon, however, the measure of the commitment that they had made began to dawn on American policymakers. Containment implied the forward defense of Europe and Asia by U.S. troops from the Soviets, who now possessed the atom bomb. Even for America at the peak of its powers, this was a frightening undertaking.